Data synchronisation patterns

Scenario

You want to save some data to a database, usually a transactional db, and take additional actions. i.e. In pseudo code:

TodoItem saveTodoItem(TodoItemSpec spec) {

// begin transaction

TodoItem item = todoItemRepo.save(spec)

alertService.sendNewItemAddedAlert(item) // AMQP

auditService.recordItemAdded(newAuditEntry(item)) // HTTP

// end transaction

}

If we wrote the above code we have a few problems.

- If the transaction cannot commit for any reason we have made a http call and placed an item on to a queue.

- If the

auditService.recordItemAddedthrows an exception we still have a message on our AMQP broker.

We might be tempted to try and ‘fix’ the issue by changing the code to:

TodoItem saveTodoItem(TodoItemSpec spec) {

// begin transaction

TodoItem item = todoItemRepo.save(spec)

// end transaction

alertService.sendNewItemAddedAlert(item) // AMQP

auditService.recordItemAdded(newAuditEntry(item)) // HTTP

}

Possibly by writing the code as above or using commit hooks in our library / framework of choice.

We still have issues however

- We might commit our transaction then shutdown our app, meaning we have an entry in the database with no audit record or alert sent

- If

alertService.sendNewItemAddedAlertthrows not only do we not create our audit but we probably throw an exception / return and error code implying thesaveTodoItemfailed when in fact it is there in the db Lets now go over strategies to deal with this.

Solutions

Who gives a shit

Its important to note this isn’t something that always needs to be solved. All solutions that actually solve the problem in a reasonable manner increase the complexity. Maybe this code is called every minute doing the exact same thing and missing a run or two doesn’t matter. Don’t invent requirements of consistency where they do not exist.

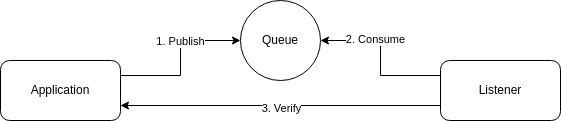

Verify after publish

The idea behind this is to always publish information to a queue then process with a delay. The listening application can then verify the data,

Application

Application

TodoItem saveTodoItem(TodoItemSpec spec) {

// begin transaction

TodoItem item = todoItemRepo.save(spec)

alertService.sendNewItemAddedAlert(toAlert(item)) // AMQP

auditService.recordItemAdded(newAuditEntry(item)) // AMQP

// end transaction

}

Listener

void handleNewItemAddedAlert(AlertSpec alertSpec) {

sleep("60seconds")

Optional<TodoItem> item = todoItemClient.getTodoItem(alertSpec.getTodoItemId());

if (!item.exists()) {

return

}

// Rest of logic

}

The idea here being if the transaction commits and successfully then we have 2 items on our queues. These items can be removed from the queue after 1 minute and verify the transaction was successful.

If the transaction did not succeed we may end up with messages on our queue anyway. When these are processed they will attempt to verify the success of the transaction and fail. These messages should be discarded.

Pros

- Simple to write assuming you are already using queues

- Plays nice with immutable data stores / event sourcing model (i.e. no updates / deletes)

Cons

- Latency - You don’t actually have to wait 60 seconds per message only 60 seconds since message was put on queue but even so you still need to wait. Without waiting you might call back too early before the transaction has committed and assume it failed when it is still in fact in progress.

- How to decide / set the timeout - In the example above I used 60 seconds but what if the transaction took longer than 60 seconds? Messages would be received, it would be assumed that the transaction had done a rollback and the message would be discarded. The transaction might complete and now we have lost a message. Need to account for this somehow.

- Doesn’t work naturally for updates, only creates - A create can be verified at a later date, is it there or not, an in place update cannot be reliably verified after the fact without additional tracking tables. For example we could have a table of transaction uuids that we commit to and then call back to verify present in that table or not.

State machines

You can use a state machine to track the state and pass data between them. Completely made up pseudo code syntax:

void saveTodoItem(TodoItemSpec spec) {

CreateTodoItem create = createTodoItemState(spec);

transition (create) {

case start -> context.record("item", todoItemRepo.save(spec))

case makeAlert -> context.record("alert", toAlert(context.get("item")))

case sendAlert -> alertService.sendNewItemAddedAlert(context.get("alert"))

case sendAudit -> auditService.recordItemAdded(newAuditItem(context.get("item")))

}

}

The key here is each operation is in its own state and some library or framework takes ownership of tracking the states and advancing, retrying where needed and working across app shutdowns / startups. See Netflix Conductor, Temporal, Spring Statemachine for more info. The state machine approach can also be done manually with no frameworks if the states are simple and you are using queues.

void saveTodoItemFromQueue(TodoItemSpec spec) {

// Walk through steps of saving items, creating alert, sending audit

// Ack message from queue at end

}

Pros

- Battle tested open source tooling exists for this.

- Tooling often comes with good observability, ability to see how many in flight state machines there are and at what states with what data.

Cons

- State machine libraries are often a significant departure from the previous way of writing code. They can come with additional infrastructure requirements, needing somewhere to queue messages, track states and their inputs / outputs etc.

- The ‘state’ of your application is now persisted between runs, previously only had to consider data that was stored in databases and on queues when updating version of your app, now when changing a state machine is that a new version of the same state machine or a different machine? This is just some extra complexity to be aware of not a deal breaker.

- Care needs to be paid to the invocation of the state machine. None of the patterns on this page can possibly work without idempotence however its easy to miss the state machine creation itself also needs to be made idempotent.

Notes

- This is a good solution if this is going to be a common problem, or you are generally heading down the path of orchestration over co-ordination.

Change Data Capture / WAL Log Tailing

As in the example at the top of the page often there is a primary datastore that is being used, be it an RDBMS or NoSQL solution like Cassandra, HBase, Mongo etc.

A common pattern (though not in every database) is to have a Write Ahead Log (WAL), or Journal that writes are written to. This is normally used for replication and crash recovery.

This can be used to track the changes made and react to them.

Application

TodoItem saveTodoItem(TodoItemSpec spec) {

// begin transaction

return todoItemRepo.save(spec)

// end transaction

}

Change Data Capture Service

void receiveWal(Wal wal) {

List<ChangeEvent> events = parse(wal);

emitEvents(events);

}

Listener

void alertOnTodoItemCreate(ChangeEvent changeEvent) {

if (changeEvent.type() == CREATE) {

alertService.createAlert(createAlert(changeEvent.getObject()))

}

}

Pros

- Handles the transactionality for you in that transactions that don’t commit are not in the WAL (in most cases, other cases might record the absence of commit in WAL either way its possible to tell)

Cons

- Requires a database with a journal or wal

- Requires understanding the structure of the journal or wal and keeping up to date with this (handled by open source libraries such as Debezium)

- Only information that was stored is available. For example in the example we are using you can create an audit entry and alert from just to the

TodoItem. What if we needed the current logged in user as well but that is not a column in the database?

Notes

- This is a great fit for problems like replicating data from one store to another for different querying such writing to RDBMS and then replicating to a column store or other form of storage.

Transactional Outbox

If the primary store is a transactional database we can piggy back off the transaction to ensure eventual consistency.

TodoItem saveTodoItem(TodoItemSpec spec) {

// begin transaction

TodoItem item = todoItemRepo.save(spec)

var alertIntentId = outboxService.saveIntent("sendAlert", createAlert(item));

var auditIntentId =outboxService.saveIntent("recordAudit", newAuditEntry(item));

// end transaction

alertService.sendNewItemAddedAlert(createAlert(item)) // AMQP

outboxService.removeIntent(alertIntentId);

auditService.recordItemAdded(newAuditEntry(item)) // HTTP

outboxService.removeIntent(auditIntentId);

}

Now when we run our code in a single transaction we save our todoItem, and our intent to send an alert and our intent to send an audit entry. For the happy path we try to send them after the transaction has committed. All we need now is a recovery mechanism incase the app is shutdown or is killed after our transaction commits.

@Scheduled("call every minute")

void backGroundMethod() {

List<Intent> intents = outboxService.findIntentsNotSent();

for (Intent intent : intent) {

switch (intent.type()) {

case "sendAlert" -> alertService.sendNewItemAddedAlert(intent.getPayload())

case "recordAudit" -> auditService.recordItemAdded(intent.getPayload())

}

outboxService.removeIntent(intent.getId())

}

}

Pros

- Simple to code and understand.

- Requires no additional infrastructure or rewrite from using http to using queues or other technology.

- The pattern is language agnostic and therefore can easily be followed in polyglot organizations.

Cons

- You need a transactional database for this otherwise we are back where we started with some rows being inserted while others are not.

- You now have a queue in your database and everything that comes with it, monitoring and concurrency.

- The above code is quite simple but you still probably need some additional logic if you want to support high (think 10,000+ transactions per second with this approach).

Queue first / Eventing

If you are building an Event Sourcing application everything is first an event before it is written to a database. So the original example would look more like:

void createTodoItem(TodoItemSpec spec) {

validateSpec(spec);

eventsService.createEvent(new TodoItemCreationEvent(spec));

}

void onTodoItemCreationEventUpdateDb(TodoItemCreationEvent event){

todoItemRepo.save(spec);

}

void onTodoItemCreationEventCreateAlert(TodoItemCreationEvent event){

alertService.createAlert(createAlert(event));

}

void onTodoItemCreationEventCreateAlert(TodoItemCreationEvent event){

alertService.createAlert(createAlert(event));

}

This assumes however that we are happy with all 3 happening in parallel in which case some events might appear / be processed before others. For example the audit entry might appear before it can be seen from the todoItemRepo.

If we don’t want this we need to introduce a 2nd event say TodoItemCreatedEvent which will be emitted post save ala:

void onTodoItemCreationEventUpdateDb(TodoItemCreationEvent event){

TodoItem item = todoItemRepo.save(spec);

eventsService.createEvent(new TodoItemCreatedEvent(item));

}

Note we are now back to needing to perform 2 actions at which point we are falling into one of the solutions from above.

The summary here is event sourcing needs to be paired with a solution to this problem it is not a solution itself.

Closing Thoughts

That is by no means exhaustive just some of the common approaches I have seen. Recommendations are always dangerous given lack of knowledge about requirements, volumes etc but that said my preferred order for the generic case is:

- Transactional Outbox

- State machines

- Change Data Capture / WAL Log Tailing